Did you miss the silver rally?

Quick notes before you play catch up

Popular daily, Gujarat Mirror surfaced that at least 44 trading firms have become insolvent by being on the wrong side of the trade with silver. They have accumulated losses exceeding rupees 3500 crores, as per sources.

Gujaratis do take big bets on their conviction.

To better understand the silver market, we recently met two Marwari brothers who have been running manufacturing plants for silver coins and utensils since a decade. Mid of 2024, both of them diverged paths and took two very different bets.

One of them doubled his production capacity, fully convinced that the retail demand will hold up despite rising prices.

The other one sold his manufacturing company and other assets, converted everything to physical gold and silver, and just held onto it. And, he has practically doubled his net worth in 2025 alone.

Both have been on the right side of the trade.

What did the Gujarati traders miss that these two brothers saw clearly? It’s worth having a look.

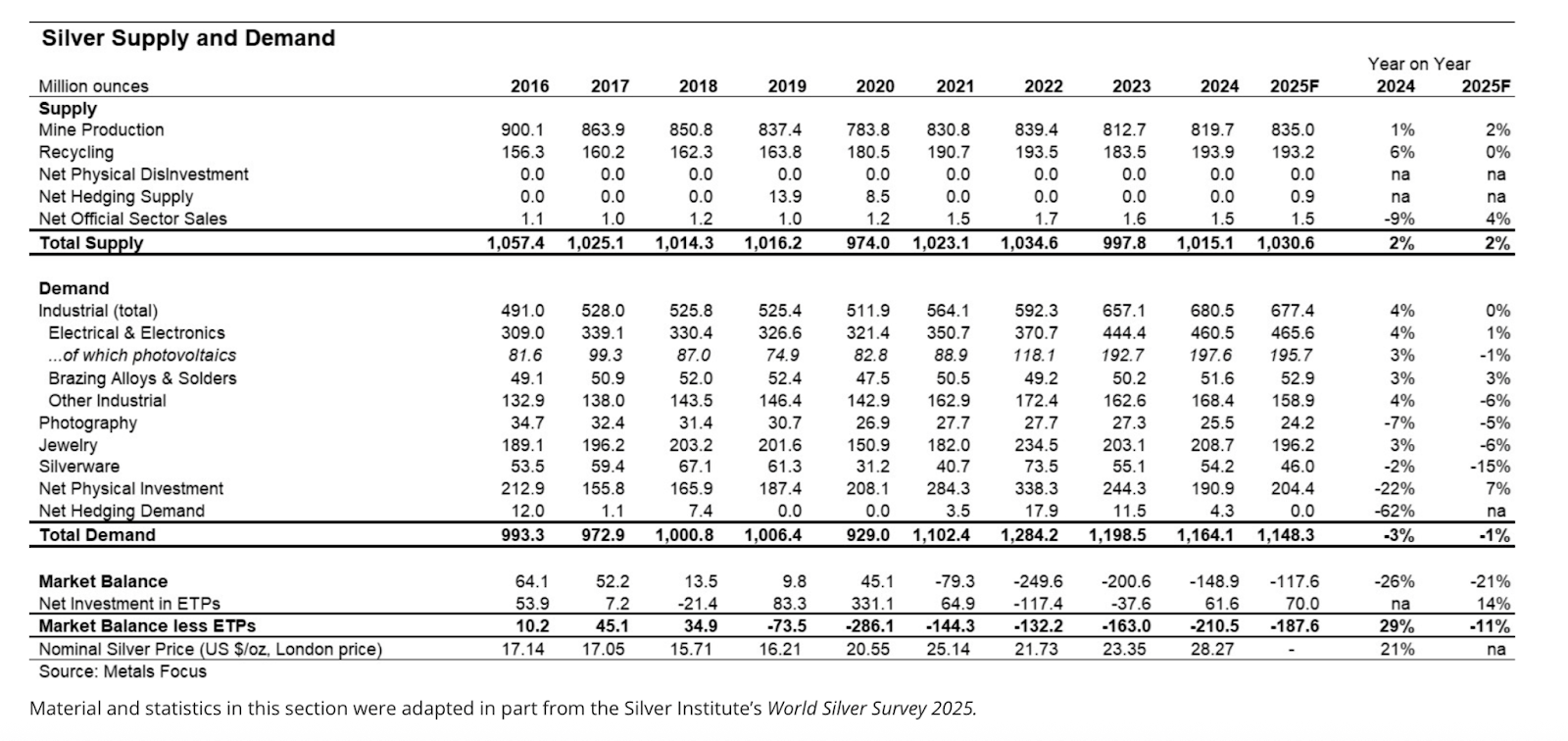

Popular narratives state that the demand for silver is rising due to its usage in electronics, cars, solar panels and jewellery, while the supply has been more or less stagnant. This explanation is broadly correct, but let’s throw some more light on the underlying mechanics.

Silver is not a commodity that responds cleanly to price signals, and that single fact explains more about the 2025 repricing than any chart pattern or macro narrative.

Most silver is not mined because someone wants silver…most of it (approx 60-80%) is produced as a byproduct of mining copper, zinc, lead, and gold. That means higher silver prices do not automatically bring new supply to market. Copper miners or zinc producers do not accelerate projects because silver looks tight, they simply accept better byproduct economics on what they were already producing.

This structural rigidity matters. It means that when demand rises or inventories fall, the market cannot rely on a quick supply response to restore balance. Adjustment happens through price, not volume. And when that adjustment finally arrives, it tends to be abrupt.

This is what has played out in 2025.

For several years, the silver market absorbed structural deficits quietly. Demand exceeded supply, but above-ground inventories acted as a buffer. Large users and financial participants could source metal from warehouses without forcing miners to respond. Thus, price stayed contained because it was drawing down stored supply.

Once that buffer thinned, prices started hitting new highs. .

The transition from surplus comfort to marginal scarcity is rarely gradual. Markets can appear stable right up to the point where availability becomes uncertain. That is when price starts reflecting urgency.

The first clear sign that silver had crossed that line came from London, the central hub for the global physical market. Liquidity tightened, borrowing costs rose and spot prices decoupled from futures. Critically, conditions eased only after significant quantities of metal were physically moved into London from other regions.

When a market needs metal shipped across borders to function smoothly, it is telling you that availability at the margin has become constrained. Headline vault numbers can obscure this reality. Large stockpiles may exist, but much of that metal is allocated, pledged, or structurally immobile. What matters is how much metal can be delivered quickly without disrupting the system. When that portion shrinks, the market feels tight even if total inventories look large.

While all this was playing out in London, visible inventories in China declined to multi-year lows. That removed another layer of shock absorption from the global system.

China is not just a consumer of silver, it is a critical node in the physical flow of metals. It dominates 60% to 70% of the world’s refined silver output. By allowing prices on the Shanghai exchange to rise significantly higher than Western exchanges (at one point an $8 per ounce difference), China incentivized traders to ship physical silver into the Chinese market. Once sufficient physical supply was pulled into the country, China introduced strict export licensing on January 1, 2026, to ensure the silver remains available for its domestic manufacturers.

“This is not good. Silver is needed in many industrial processes,” tweeted Elon Musk.

This sends a shock across the supply chain. Producers have reported aggressive buying behaviour from industrialists. What we saw in 2025 could be the initial leg of a longer scarcity cycle. Thus, it is important to keep an eye on the plumbing -

Where the metal is: which vaults, which countries, and whether it is free or already allocated.

How easily it moves: shipping times, export approvals, and whether metal can cross borders without friction.

The cost of access: lease rates, borrowing costs, and location premiums between London, Shanghai, and other hubs.

Who is holding it: industrial users, ETFs, traders, or strategic stockpiles.

How fast shortages show up: whether buyers pay up immediately or wait, and how quickly inventory is rebuilt after draws.

We’ll keep on sharing our observations. Stay tuned!

Really sharp breakdown of the silver supply dynamics. The byproduct angle gets overlooked way too often when people talk about commodities. I rememebr watching copper miners in Chile a few years back and realized how much of their economics depended on silver credits they barely thought about. The China export licensing move is kinda brilliant from a strategic standpoint, basically locking in domestic supply before global markets could adjust.