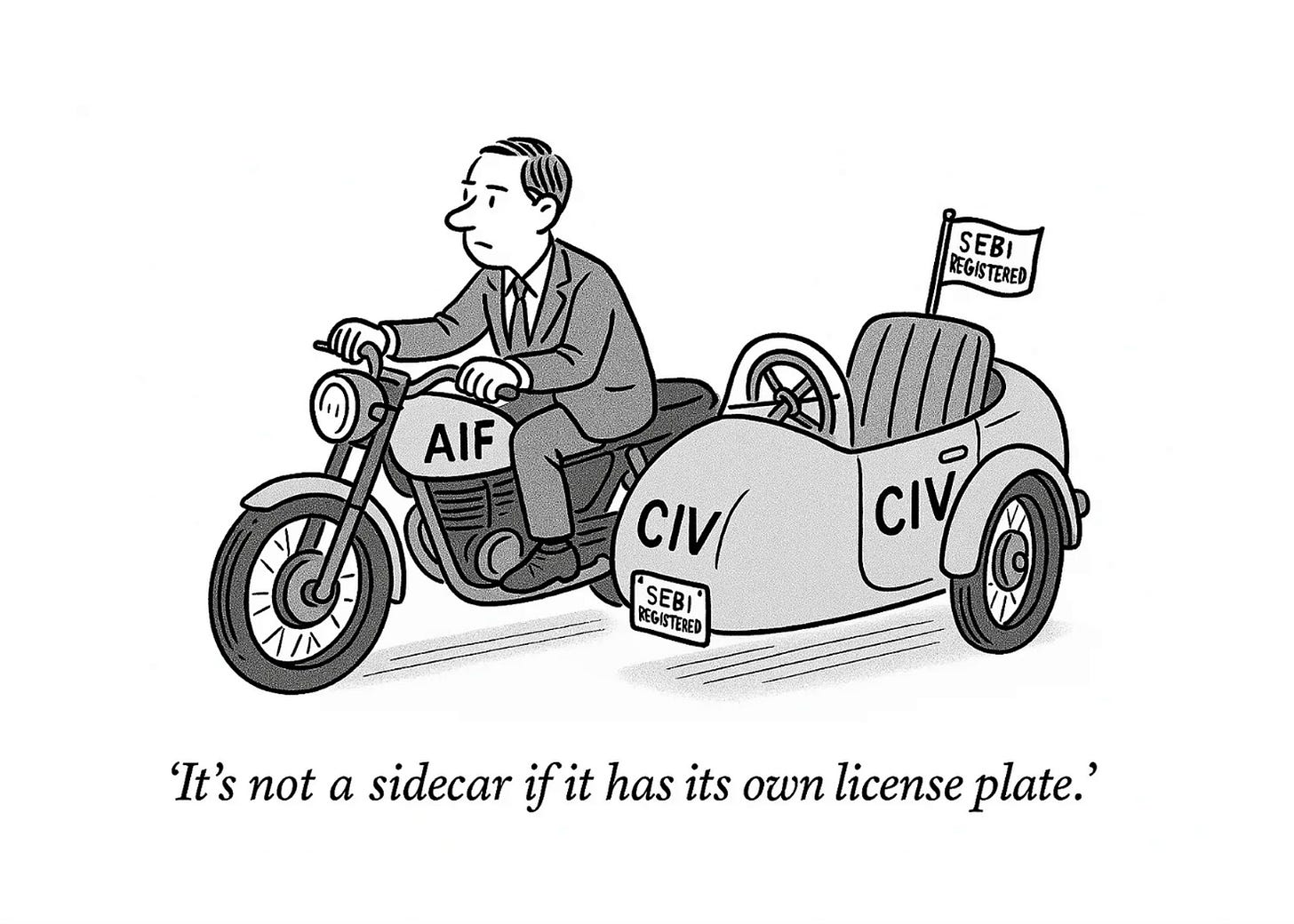

Essential Notes on SEBI’s Co-Investment Vehicle (CIV) Proposal

With commentary from Shubham Soni, Partner at Sirius Legal

SEBI has proposed a long-overdue structural fix to a well-known problem in the country’s private markets → the inefficient and compliance-heavy route for co-investments.

Under the current regime, LPs looking to participate in portfolio-level transactions alongside an AIF must do so through Portfolio Management Services (PMS). While legally permissible, the PMS route is operationally inefficient, tax-opaque, and structurally disjointed from the core AIF platform. Basically, it’s a work around.

SEBI’s fix is to introduce Co-Investment Vehicles (CIVs) - standalone schemes registered under the AIF Regulations, specifically created for individual co-investment opportunities. Each CIV would operate as a separate scheme under the main AIF, accessible only to accredited investors, governed by a shelf Private Placement Memorandum (PPM), and required to exit along with the parent AIF. The intention is to bring co-investments into the regulatory fold without compromising on alignment, oversight, or structural integrity.

As a legal construct, the proposal is sound. It eliminates the dual burden of managing PMS and AIF side by side, offers regulatory certainty under a unified regime, and provides investors with a cleaner compliance profile. The use of a shelf PPM, in particular, is a pragmatic inclusion. By allowing a standardized, pre-filed disclosure document to be reused across multiple co-investment opportunities, it balances disclosure obligations with the speed that deal-making often requires.

However, the practical limitations are worth discussing with clarity:

First, the requirement that the CIV’s exit must mirror the exit of the main AIF significantly restricts flexibility. One of the principal motivations for LPs to co-invest is the ability to tailor their exposure - both in amount and duration - to a specific asset. By mandating a coterminous exit, SEBI introduces rigidity that may deter sophisticated LPs who operate on differentiated time horizons or need liquidity options independent of the fund.

Second, the eligibility restriction to accredited investors, while defensible from a regulatory risk perspective, introduces a bifurcation in the LP base. Larger institutions will gain preferential access to high-conviction opportunities, while smaller LPs, despite participating in the same AIF, may be excluded. Over time, this can lead to governance asymmetry and alignment issues within fund structures.

Co‑Investment Vehicles (CIVs) as separate schemes under existing AIFs mark a significant and welcome regulatory shift…however, confining CIVs to accredited investors significantly narrows the current investor base and warrants re-evaluation. Furthermore, careful structuring is crucial for existing single‑scheme AIFs looking to leverage the CIV framework and manage tax implications at fund, CIV and investor levels.

Shubham Soni, Partner at Sirius Legal

And also to highlight the most critical aspect - the unresolved question of taxation. While Category I and II AIFs enjoy pass-through treatment under Indian tax law, there is no clarity yet on whether CIVs, each operating under a separate PAN and scheme registration will be accorded identical treatment. Unless the CBDT expressly confirms pass-through status for CIVs, the risk of dual taxation, treaty ineligibility, and withholding complications (particularly for offshore LPs) remains significant. It's a crucial factor which affects IRR calculations, withholding strategies, and investor appetite. Fund managers and LPs will require advance rulings or clear administrative guidance before proceeding with confidence.

Adding to it, the operational load imposed by the CIV structure is non-trivial. Each CIV must be treated as a fully autonomous scheme from a compliance, reporting, and audit perspective. For fund managers engaging in multiple co-investments per annum, this implies a measurable increase in administrative cost and complexity. Unless firms are operating at scale, the cost-benefit equation becomes questionable.

From a governance standpoint, CIVs will raise the bar for fund managers:

Allocation policies will need to be clearly documented.

LP communications will need to be airtight.

Conflicts of interest, particularly around deal pricing, access, and disclosure must be addressed through robust internal controls.

That said, SEBI’s intent is directionally correct. Co-investments have been operating in a regulatory grey zone for too long. The proposal brings them within the fold of AIF regulation, applies proportional safeguards, and offers a legitimate, regulator-recognized path forward. For global LPs that demand transparency and legal clarity, this is a step in the right direction.

But CIVs, as currently designed, are not plug-and-play. Their viability hinges on three things: (i) explicit confirmation of tax treatment by the CBDT, (ii) flexibility on exit mechanics (possibly through managed deviation with disclosure), and (iii) administrative streamlining, especially for managers below institutional scale.