Global Funds Sour on India but the Turn May Already Be Starting

A Short Take

India’s equity market has experienced one of the sharpest reversals in global investor sentiment in recent years. After spending much of the past decade as the consensus favourite in emerging markets, India is now the single largest underweight in global emerging-market portfolios. Only about a quarter of active GEM funds still allocate more than the benchmark weight of roughly 15 to 16 percent. The rest have pulled back.

This shift has been driven by two forces. One is local: a cyclical slowdown that weighed on earnings expectations just as valuations reached peak territory. The other is global: a powerful rotation into artificial intelligence linked stocks in Korea, Taiwan and China that drew capital away from almost every other emerging market.

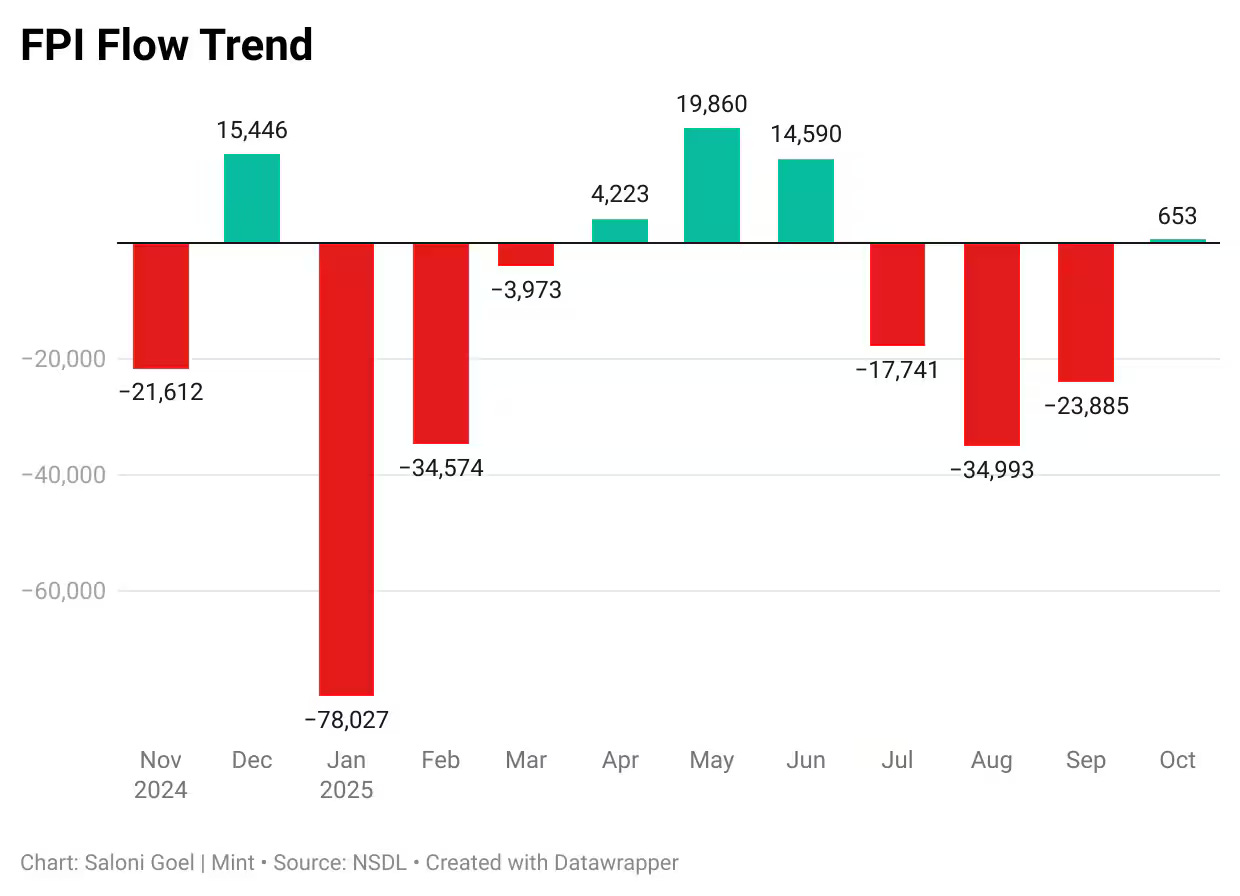

Foreign portfolio investors sold more than 30 billion dollars of Indian equities over the last twelve to thirteen months. The pullback pushed foreign ownership to multi-year lows and pushed India’s MSCI EM weight to a two-year trough. The selloff also delivered India’s worst relative performance against the EM benchmark in roughly two decades.

Yet for all the gloom in global positioning, Indian markets have remained stable. The primary reason is domestic money. Systematic investment plan flows hit repeated monthly records. Domestic institutions deployed more than six trillion rupees through the year. Equity mutual funds absorbed foreign selling with little market disruption. India’s market structure is shifting from foreign-dependent to locally anchored, a trend that makes equity flows more predictable even as global sentiment swings.

This shift in ownership dynamics is one reason global strategists are rethinking their stance. HSBC argues that India now serves as a diversification hedge for investors who feel increasingly crowded in North Asia’s AI trade. Goldman’s upgrade to overweight is grounded in similar reasoning. Once valuations cool and positioning thins out, even modest improvements in earnings or policy visibility can trigger disproportionate inflows. Goldman has assigned a Nifty target of 29,000.

The macro backdrop gives this reassessment some support. India continues to grow at about 6 to 7 percent, maintaining its status as the fastest growing large economy. Formalisation, digitisation and infrastructure expansion remain intact. Corporate balance sheets are relatively healthy. None of these structural factors has weakened during the recent period of market underperformance.

Risks remain and should not be understated. The earnings cycle must deliver the recovery analysts are expecting. Domestic flows cannot slow abruptly without exposing market fragility. Higher oil prices or a global downturn would complicate the picture. And India’s valuation premium, although moderate relative to last year, remains significant by EM standards.

Even so, markets often move ahead of fundamentals. India’s underweight status means global investors are now carrying minimal exposure to one of the most liquid and structurally stable markets in the EM universe. If broader EM inflows return or if the AI-centric trade loses momentum, the rebalancing effect alone could drive meaningful foreign buying.

For now, India sits at an unusual intersection. It is the least favoured major emerging market at a time when its domestic investor base is stronger than ever. For long-term allocators, that combination has historically been a precursor to improved performance. Whether this cycle follows the same pattern will depend on how quickly the earnings narrative turns and how durable domestic support proves to be.