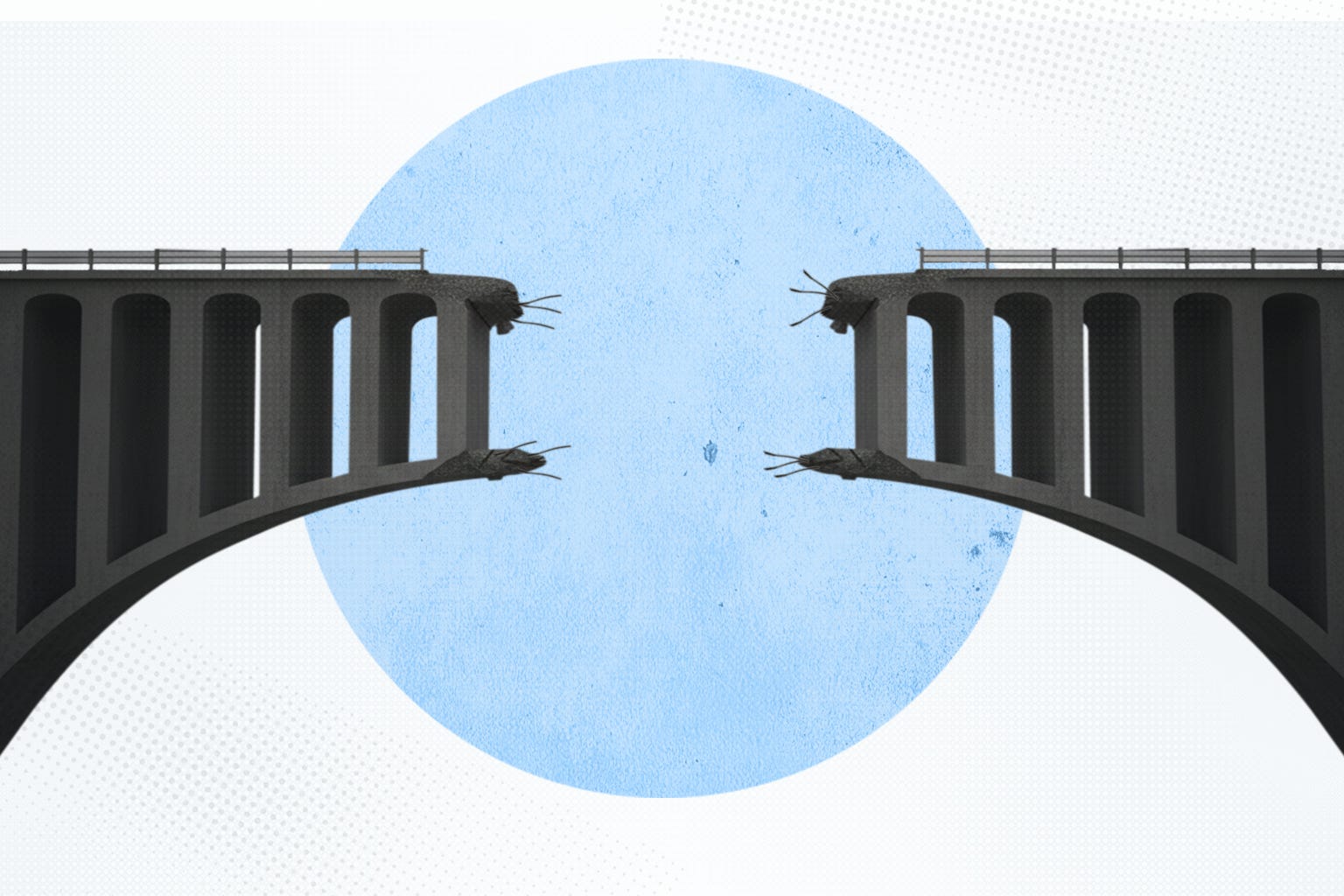

The Missing Middle

Who is funding Series C and later rounds?

A healthy venture market resembles a relay race. Capital flows smoothly from seed to Series A, from A to B, from B to C and beyond, until the baton is carried across the finish line through IPOs or strategic acquisitions. Lately, the baton is being dropped at the growth stage. Series C and later rounds, the critical layer of financing that allows young companies to scale into durable public firms or strategic assets, have slowed to a trickle. Financing is vibrant at the early stage and aspirational at the end, but dangerously thin in the middle where companies are supposed to prove their ability to scale.

This absence of growth capital is forcing founders into increasingly difficult choices. Expansion plans are being delayed, global ambitions shelved, and profitability drives accelerated long before businesses are actually ready. Insider rounds do buy time, but they are no substitute for genuine growth funding. They risk permanently being a ‘startup’.

The numbers illustrate the severity of this breakdown.

After the exuberant highs of 2021 and 2022, when Indian startups raised record sums, 2024 marked one of the weakest years in recent memory. In the first half of 2025, Indian tech startups raised just $4.8 billion, down about a quarter from the same period a year earlier. Within that, late-stage rounds contributed only $2.7 billion, a fall of 27% year on year. Early-stage funding has proved resilient, even buoyant in some verticals. It is the growth rounds i.e. Series C and beyond, have become hardest to sustain, precisely where the capital need is highest.

Much of this reflects the retreat of global crossover funds that once underpinned India’s late-stage momentum.

Tiger Global, Sequoia, and SoftBank used to provide the $50 - 100 million cheques that carried companies across the growth chasm. Today, all three have pulled back. Tiger, after a frenzied run in 2020 - 21, slashed its exposure during the 2022 - 23 funding winter and has since returned only selectively, focusing on defending its winners rather than backing new names. Sequoia’s restructuring in 2023, which spun off its India arm as Peak XV Partners, coincided with a deliberate downsizing of its growth fund by nearly half a billion dollars. And SoftBank, scarred by multi-billion-dollar losses in Oyo, Ola, and Paytm, has retreated even more decisively. In their absence, domestic funds have not yet developed the balance sheets or appetite to replace them.

The deeper issue, however, is not simply who provides the money, but why growth rounds have become so hard to price.

The exuberance of 2020 - 22 is the first culprit. Late-stage rounds in those years were priced for perfection, assuming tripling revenues every year and quick paths to profitability. When reality fell short, the markdowns were brutal. Byju’s and PharmEasy, once flag-bearers of Indian innovation, lost 70 - 80% of their peak value. Investors came to see overpricing at the growth stage as a systemic risk.

Public markets, meant to validate private optimism, have instead undermined it. The IPOs of Zomato, Nykaa, and Paytm were heralded as milestones, but their shares plunged 40 - 70% below issue prices within months of listing. A private valuation of $2 billion no longer looked credible when listed peers traded at half the multiple. Growth rounds, which depend on bridging the optimism of private markets with the discipline of public markets, thus became almost impossible to underwrite.

The exit pipeline has also narrowed to a dangerous degree. In 2024, India produced only three tech IPOs above $500 million, compared with more than twenty in 2021 and 2022. Billion-dollar mergers remain rare, with only a handful of domestic acquirers able or willing to absorb startups at scale. Without reliable exits, late-stage financing becomes bridge capital with no bridge, risk without liquidity. For global funds already under pressure from their own limited partners to return cash, that is not a risk worth taking.

Governance failures have compounded the problem. Scandals in edtech, layoffs across consumer internet firms, and accounting lapses in fintech have eroded confidence further. For investors already wary of valuations and exits, weak compliance and fragile governance are the final deterrent. The cumulative result is a missing middle in motion: Series C and beyond are harder to price, slower to close, and increasingly dependent on defensive insider rounds rather than fresh inflows.

Some have suggested that mergers and acquisitions could plug the gap.

In theory, this is true: a healthy acquisition market can serve as a substitute for late-stage funding, recycling capital back into the ecosystem. In practice, India’s M&A market is underdeveloped. The country recorded about $50 billion in total deal value in the first half of 2025, but less than 4% of that involved technology. By contrast, in the United States and Europe, technology typically accounts for a quarter to a third of annual M&A. The reasons are obvious: few Indian startups are profitable enough to attract strategic buyers; domestic corporates hesitate to acquire startups, fearing integration risk; and regulatory frictions around foreign investment and taxation add further complexity. Culturally, many founders still view acquisition as failure rather than strategy. The result is an acquisition market too thin to serve as a dependable exit channel.

Yet the ingredients for a stronger middle do exist.

India has deep entrepreneurial talent, rising pools of domestic capital, and corporates with expanding balance sheets. What it lacks is coordination and intent.

Stage-specific growth vehicles, backed by sovereign wealth funds, pensions, and insurers, could help.

Incentives for corporate India to acquire startups for technology, talent, and intellectual property, not just revenue, would deepen the acquisition pipeline.

Simplifying regulations around share transfers and foreign investment would accelerate deal-making.

Reforming IPO frameworks to accommodate high-growth companies, even before full profitability, would reopen the listing window.

The difficulty of growth rounds is that they straddle the most fragile part of the venture cycle: too late for narrative-driven optimism, too early for public-market validation. That fragility has been magnified by valuation collapses, IPO disappointments, governance lapses, and thin exit channels. Unless capital pools and exit pathways are rebuilt, India risks creating a startup ecosystem that begins strong but fails to deliver enduring enterprises.