Too Big To Stay Small

Why Manufacturing Hasn’t Taken Off In India (Yet)

Few paradoxes in the global economy are as striking as India’s growth story. Over the past three decades, our country has become closely associated with the rise of services. A nation of coders, consultants and call centers now powers the back offices and IT systems of companies around the world. From Infosys and TCS to the booming startup ecosystems in Bengaluru and Gurugram, India has earned a reputation as a global services powerhouse. Beneath this success, however, lies a persistent weakness: the country has struggled to build a strong manufacturing base.

This contrast is even more pronounced when compared to East Asia’s development trajectory. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan in the postwar decades, followed by China and Vietnam. All experienced deep economic transformation through manufacturing-led growth. These countries built industrial ecosystems, created millions of stable jobs, and used export-driven factories as the foundation for broad-based prosperity. Manufacturing played a central role in their climb from poverty to middle-income and in some cases, high-income status.

India appears to have many of the same inputs. It has a large labour force, entrepreneurial energy, a growing domestic market and a policy framework that has supported liberalization since 1991. Despite this, the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP has remained flat, stuck between 15 and 20 percent. Exports have expanded slowly and the sector has made only a modest contribution to employment.

Why has India fallen short of its manufacturing potential? Why have services taken center stage while factories have remained on the sidelines? And in today’s shifting global, what is the path forward for us?

This long-form post examines these questions through the lens of East Asia’s industrial experience, India’s policy and institutional environment, and the global economic context that will shape the next phase of development.

The East Asian Playbook

When people talk about the “East Asian miracle,” it often sounds like a story of exceptionalism. It suggests the rapid industrialization and sustained economic growth achieved by countries like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, China, and Vietnam through strategic policies. Some chalk it up to culture, others to timing…but if you strip away the clutter, what remains is a clear and replicable strategy. This strategy proved effective across a variety of political systems and historical periods. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, China, and Vietnam all followed a version of the same three-step approach: fix agriculture, build competitive export manufacturing, and use finance to reward performance. Let’s understand this approach.

Start with the land

The first move was deceptively basic: land reform. After WWII, Japan broke up large estates and handed land to tenant farmers. Productivity shot up because ownership tends to have that effect - people invest more when the returns are theirs to keep. South Korea and Taiwan did the same in the 1950s. These actions were not driven by ideology…they were all practical measures aimed at laying the groundwork for a stable and productive economy.

Higher rural incomes meant people could buy basic goods such as clothes, soap, radios…which gave early manufacturers a domestic market. More importantly, smallholders saved. Those savings became the early capital pool that helped fuel industrialization. The countries that skipped this step, like the Philippines, never really built that foundation. Rural inequality persisted and the move to a manufacturing economy never got out of second gear.

Export or die

Once the agricultural base was in place, the focus shifted to manufacturing - but with a twist. East Asia didn’t protect its firms forever behind high tariffs and closed markets. Instead, governments pushed companies into global markets fast and hard. In Korea, if a firm wanted cheap credit or tax breaks, it had to hit export targets. If it missed, the support disappeared. No second chances. Hyundai learned to build cars the hard way…by selling to Americans who didn’t care about excuses.

Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry, also commonly referred to as MITI did something similar. It picked promising sectors, backed early movers, and kept reallocating resources until the best firms rose to the top.

Taiwan built its industrial base through contract manufacturing. It started out assembling electronics for foreign brands and then climbed the ladder.

The message here was super straightforward. Compete globally, or don’t compete at all. International markets forced companies to improve or disappear. That pressure created muscle for scale, quality and productivity. The more they produced...the sharper they got.

Finance with a spine

This is where many developing countries fall apart. They make credit cheap, then hand it to politically connected firms that simply have no reason to improve. East Asian economies in focus took a harder route. Credit was cheap, yes, but only for companies that delivered.

In South Korea, banks were tools of industrial policy. They pushed capital into targeted sectors, but they also pulled it out quickly when companies missed targets.

In Taiwan, lending was less centralized but just as conditional.

Even China, in its own way, followed this principle. The state funneled resources into priority industries and didn’t hesitate to shift course when results fell short.

The goal was to provide firms with opportunities to expand while ensuring they remain accountable. That’s how you get real industrial depth - by balancing pressure and support that comes with strings attached.

Systematic effort

None of this was intuitive. It was coordinated and enforced. And it worked across systems that ranged from postwar democracies to military regimes to single-party states. The model created the conditions for success. Where governments kept their nerve and stayed focused on results, manufacturing took off. Where they drifted, the story played out very differently.

India’s Divergent Path

India’s growth path looks very different from the East Asian template. It started industrialization without a strong rural base, shifted early into services, and left many core policy bottlenecks unresolved. The result has been a modern economy with impressive digital and financial services, but limited manufacturing depth.

Land reform remained incomplete

India attempted land reform in the decades after independence, but the results were uneven. Some states, like West Bengal and Kerala, managed to redistribute land and formalize tenancy. In most of the country, however, powerful local interests blocked real change. Laws capping landholdings were diluted, enforcement was weak and loopholes were used to retain control. Millions of farmers remained stuck in low-productivity agriculture. That continues even today.

Farmers with small plots and uncertain ownership had little reason to invest. Rural productivity stayed low. Incomes remained limited. This meant there was less demand for manufactured goods like clothing, tools, and appliances, the same kinds of goods that helped early factories grow in East Asia. Without that demand, India’s domestic market for basic manufacturing stayed shallow.

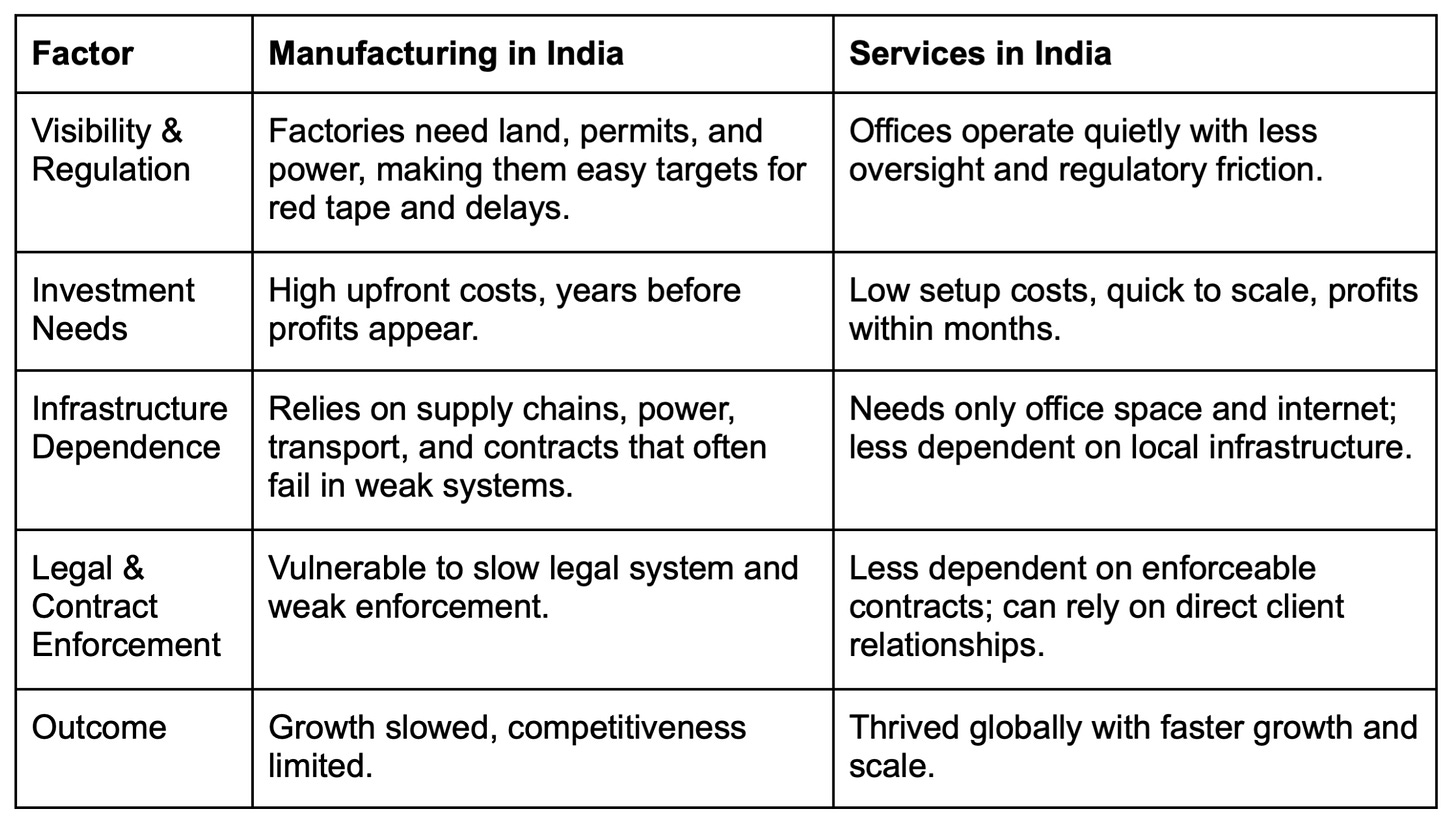

Services grew, manufacturing stalled

As the economy liberalized in the 1990s, services began to grow quickly. Sectors like software, finance, telecom, and professional services required relatively little land and could scale with limited physical infrastructure. These industries operated in clusters, attracted educated talent, and avoided many of the complications tied to state regulation.

Manufacturing, in contrast, struggled. It required land acquisition, power supply, transport logistics, and a stable regulatory environment. These dependencies made it far more vulnerable to bureaucratic hurdles and rent-seeking behavior.

Policy choices closed off key avenues

India’s industrial strategy in the early decades focused heavily on self-reliance. The goal was to protect domestic producers and avoid foreign dependence. This led to a regime of high tariffs, import licensing, and restrictions on foreign capital. The market was fragmented, competition was limited, and scale remained elusive.

In the 1970s, controls became even more rigid. The license raj added layers of approvals for everything from capacity expansion to product lines. The MRTP Act placed restrictions on the size of firms. Labor-intensive industries were reserved for small-scale producers, which limited their ability to grow and compete. The entire system discouraged investment, innovation, and consolidation.

When reforms finally arrived in 1991, the focus was on trade and capital flows. Tariffs were reduced, foreign investment was welcomed in some sectors, and the private sector was given more autonomy. However, critical areas such as land acquisition, labour regulation, and contract enforcement were left largely untouched. These gaps made it difficult for manufacturing to scale, especially in export-oriented and labour-intensive segments.

Liberalization lacked structural depth

The post-reform period has created space for growth and the private sector has responded. But the institutional foundation remains shaky. Land markets are fragmented and politically sensitive. Labor laws make it costly to hire or restructure workforces. Courts move slowly…making contract enforcement uncertain. These factors raise the cost of doing business in manufacturing, especially in sectors that depend on scale and reliability.

Investment, thus, flows into areas where these constraints matter less. Technology services, telecom, finance, and consumer goods all have expanded. But the industrial sector, particularly small and medium manufacturers, continues to face high entry barriers and low productivity traps. Despite policy programs and new initiatives, the structural roadblocks have never fully receded.

The 12 Structural Roadblocks

Labor - Rigid Rules, Limited Flexibility

India’s labor regulations discourage firms from scaling up. For instance, any factory with over 100 workers cannot lay off employees without government permission – a clearance that is “rarely granted”. Such rules drive up costs for midsized firms and encourage businesses to stay below the 100-worker threshold to avoid red tape. Multiple labor laws kick in at low employee counts (some as low as 10 or 20 employees), adding compliance burdens early. Furthermore, minimum wage rates differ by state and job type, creating a maze of rules that is cumbersome to administer. The net effect is a disincentive to scale – companies often deliberately remain small or rely on contract workers to sidestep rigid hiring and firing laws.

Land - Expensive, Fragmented, Badly Planned

Acquiring industrial land in India is costly and complex. Government land policies have unwittingly encourage[d] rampant land speculation, inflating prices so much that huge portions of project budgets go just to land acquisition. Land in India often costs far more than its productive value, and clear titles are hard to come by due to frequent disputes. Urban planning has failed to earmark enough land for industry in or near cities, so many factories end up in far-off locations. Companies increasingly avoid buying land altogether – instead leasing ready sites to circumvent land acquisition challenges and achieve faster operational timelines. Distant factory locations also mean longer supply lines and difficulty attracting skilled labor. In short, fragmented land markets and poor planning have made securing industrial land a major hurdle, driving up costs and reducing efficiency.

Electricity - Expensive and Unstable

Manufacturers in India face power costs and reliability issues that undermine competitiveness. Industrial users pay about ₹4.8 per kWh (approximately $0.11), a rate on par with OECD countries despite India’s far lower income levels. These high tariffs are partly due to cross-subsidization – industry bears higher charges so residential and agricultural users pay less. Even at such prices, supply quality is patchy. India ranks near the bottom globally for electricity reliability, placed 108th out of 141 countries in one survey of power supply quality. Frequent outages force firms to invest in generators and backup systems, further raising operating costs. Moreover, India’s grid is still predominantly coal-fired, making it hard for factories to meet rising global carbon standards. Inconsistent, pricey electricity is thus a double burden – it inflates costs and impedes the round-the-clock stability that modern production requires.

Infrastructure - Better, But Still Expensive

Despite improvements in highways, ports, and freight corridors, India’s logistical costs remain among the highest in the world. Moving goods across India costs an estimated 14%-18% of GDP, far above the 8%-10% typical in developed economies. Last-mile transport is often slow and roads congested, eroding the gains from new expressways. Port turn-around times, while improving, have lagged global benchmarks - ships in India’s ports are used to spend 2–3 days to turn around vs. 10–12 hours globally (though initiatives like the Gati Shakti plan are starting to address this). Cold storage and warehousing networks are highly fragmented; over 90% of India’s cold chain logistics sector is privately owned and lacks standardization. This patchwork leads to spoilage, delays, and inefficiencies in supply chains. In summary, infrastructure has come a long way, but fragmented logistics and high transport costs continue to act as a tax on Indian manufacturing.

Finance - Too Costly, Too Tight

Interest rates for business loans are high, often in the double digits, putting Indian firms at a cost disadvantage (rates of 14-16% for capital loans). Working capital is hard to come by at affordable rates. MSMEs especially face delayed payments from large buyers, tying up their funds for months. It’s common for MSMEs to wait well beyond 45 days for payment, which forces them to borrow at high interest just to stay afloat. These delays have become so chronic that new rules now sanction large companies for not paying small suppliers on time. While credit is available in the banking system, it seldom comes at the speed or cost manufacturers need. The result is frequent cash-flow crises. Companies must hold excess cash or rely on informal lending to bridge gaps, raising their operating costs and risk.

…By bridging the early to mid stage funding gap and backing founders in manufacturing and infrastructure with the discipline to execute globally, we can unlock the second growth engine of the Indian economy.

Vignesh Shankar, Founder at a99, previously led turnaround and transformation projects for industrial and engineering businesses across Asia

Trade - Protected Inputs, Weaker Outputs

India’s trade policy has often favoured import substitution, which means high tariffs on many inputs and intermediates. These duties raise the cost of crucial raw materials and components for domestic producers. Studies show that India’s tariffs on manufacturing inputs are much higher than those of competing nations, directly translating into costlier finished goods. For example, electronics manufacturers in India face steeper import duties on components than firms in China or Vietnam – undermining their export price competitiveness. The intent is to nurture domestic industries, but the flip side is that expensive inputs make Indian exports less competitive abroad. India’s reluctance to fully embrace free trade agreements (it notably stayed out of RCEP, a major Asia-Pacific trade pact) further limits access to cheaper inputs and larger markets.

Legal Enforcement - Unreliable and Slow

Contract enforcement in India is notoriously slow, which is a serious impediment to manufacturing and supply chain reliability. If a supplier fails to deliver or a partner breaches a contract, the legal resolution can take years. According to the World Bank, resolving a commercial dispute through an Indian court takes about 626 days on average. Such delays make just-in-time production and multi-party agreements risky, since there’s little recourse if things go wrong. Companies cannot count on timely remedies, so they often resort to informal arrangements or avoid complex contracts altogether. The unpredictability extends beyond contracts – enforcement of environmental and safety regulations can be equally uneven, with honest firms sometimes feeling penalized while violators go unchecked. It’s hard to build efficient, tightly coordinated supply chains without assurance that agreements and rights will be upheld promptly and fairly.

Scale - Too Small to Learn

Indian manufacturing is dominated by small, sub-scale operations. Most factories never reach the size where economies of scale and learning-curve efficiencies kick in. In labor-intensive sectors from apparel to toys, India has a “missing middle” – countless tiny workshops and very few giants. This fragmentation means each firm has limited capacity to invest in modern machines, R&D, or process improvements. They also don’t benefit from volume discounts on inputs or the productivity gains that come with repetition and refinement of large-scale production. In effect, many firms are stuck in a low-productivity trap, producing small quantities with cheap labor and outdated methods. Such firms find it hard to compete internationally or even against bigger domestic players. The lack of scale also stunts the development of robust supplier networks and industrial clusters. Everyone remains too small to significantly learn, innovate, or boost productivity over time.

Tax - GST Still Glitchy

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) was meant to unify India’s market, but implementation hiccups continue to plague manufacturers. One major pain point has been the refund of input tax credits, especially for exporters and firms in an inverted duty structure (where inputs are taxed more than outputs). In practice, companies often wait months for GST refunds, locking up their capital. Many businesses complain that legitimate credits get held up due to technical mismatches in return filings or overzealous fraud checks. These delays strain cash flow in crucial times. Although systems are improving – with the GST Council recently moving to fast-track 90% of certain refunds upfront – small manufacturers still find the tax compliance process complex and occasionally arbitrary. There have been cases of tax credits being denied because of minor clerical errors, or rule interpretations changing with little notice. While GST is a landmark reform, its “glitches” in execution mean that manufacturers spend undue time and resources on compliance and are wary of the tax regime’s unpredictability.

Global Integration - More Friction Than Flow

India’s manufacturing sector remains only partially integrated into global value chains. Policies and regulations add friction to cross-border flows of goods, capital, and talent. For example, strict visa rules and bureaucratic hurdles make it difficult to swiftly bring in foreign technical experts or managers for local plants (and similarly hinder Indian professionals from easily working abroad in manufacturing roles). Caps and approval requirements on external commercial borrowing and foreign direct investment in certain sectors also create hesitation for multinational supply chains to fully involve India. The country has taken a cautious stance on trade liberalization – it maintains higher tariffs than many peers and has been selective in free trade agreements. Cumbersome customs procedures and standards that differ from global norms further slow down integration. In essence, where India excelled in services globalization (like IT outsourcing), manufacturing has seen more protection and inward focus. This means less foreign investment in factories, less participation in multinational production networks, and missed opportunities to export at scale.

Skills - Plenty of Workers, Few Managers

India may have no shortage of labor in general, but there is a dearth of experienced manufacturing managers and technicians. Many firms struggle to find plant managers, production supervisors, and engineers with the right expertise in operations. Part of the issue is historical – for years, bright graduates have preferred careers in IT or finance over working in a factory setting. This talent diversion has left an aging pool of manufacturing managers nearing retirement, with too few trained replacements in the pipeline. Today, companies in core sectors (steel, chemicals, automotive, etc.) report an “acute shortage” of senior management talent as they expand operations. At the shop-floor level, manufacturers also face a skills mismatch – many workers and diploma-holders lack the practical training for modern machinery and quality control processes. Employers often have to invest in months of in-house training, or poach skilled staff from competitors, which again raises costs. The abundance of unskilled labor thus masks a real constraint: a shortage of skilled operators and capable managers who can drive productivity improvements.

Federal Structure - Uneven Terrain

India’s federal setup means business rules can vary greatly from one state to another, creating an uneven playing field for manufacturers. Important areas like land acquisition, electricity distribution, labor regulation, and local taxation are influenced by state policies. Some states have been reform-minded – each pursuing independent agendas – while others lag behind. This patchwork can be confusing and inefficient. A factory in Gujarat, for example, may deal with more investor-friendly labor laws and faster land approvals than one in, say, West Bengal or Uttar Pradesh. Incentives like tax breaks or easy permissions also differ by state. As a result, companies often “state-shop” for the most convenient location. Certain nationwide reforms get held up or diluted because they require consensus across states. The recent push for cooperative federalism aims to reduce these disparities. But until that happens, India offers not one business environment but many. For manufacturers operating across multiple states, this means adjusting to varying compliance regimes – a drain on time and resources.

The Sum of the Parts

The main issue you’ve already covered is that land is super expensive, but it’s not just inflation driving up prices. Corruption and middlemen play a big role too as they push up costs way beyond the actual value. On top of that, some land deals are politically sensitive. A change in government can mean approvals get reversed or renegotiated. Different states have their own rules, and when you mix that with central laws like the Land Acquisition Act, it just adds to the confusion.

If the land is near forests, tribal belts, or eco-sensitive areas, then you need a whole set of environmental, rehabilitation, and resettlement approvals. These can take years. Even converting farmland into industrial land isn’t easy and the approvals are long and costly.

Water is another big hurdle. Industries like steel, chemicals, and textiles need a ton of it, but with scarcity and local communities also depending on the same resources, it often becomes a flashpoint.

Environmental clearances are another headache. Pollution control approvals vary from state to state, and sudden changes in rules can delay or disrupt operations.

Law and order issues make things worse. Local protests by farmers, NGOs, or political groups can drag on and even force companies to put projects on hold.

Kusharg Katal (second generation entrepreneur currently setting up his factory)

Individually, none of these barriers would be a mortal blow to industrial growth. But together they form a systemic drag that keeps Indian manufacturing in a low-equilibrium trap. These issues feed on each other – costly land and power make large-scale production less viable; small firms then don’t invest in skills or innovation; weak infrastructure and legal enforcement deter big investments, and so on. It is thus not surprising that manufacturing’s share of the economy has stagnated despite India’s vast workforce and market. Breaking out of this trap requires tackling multiple constraints in concert. If India were to even partially fix a handful of these roadblocks – say, make electricity reliable, streamline land and labor laws, and improve logistics – the impact could be enormous. Investor confidence would rise and many firms currently content to stay small might rapidly scale up. In short, the whole is worse than the sum of the parts, but that also means removing several key hurdles at once could unlock a virtuous cycle of investment, scale, and competitiveness that has so far eluded India’s manufacturing sector.

Why Services Succeeded Where Manufacturing Struggled

Current Global Realities

The world has entered a turbulent new phase of trade and geopolitics. For India, that means both risk and opportunity. Whether it seizes the moment depends on how it navigates the complexities.

Geopolitics and the "China‑plus‑1" gap

India briefly looked poised to capture the "China‑plus‑1" opportunity. Apple’s Q2 2025 data shows that 44 % of iPhones imported into the U.S. were assembled in India, compared with just 13% a year earlier, while China’s share plunged from 61% to 25%. That shift reflects global efforts to diversify supply chains.

Yet this window is narrowing fast. The U.S. imposed steep new tariffs-up to 50 %-on a wide range of Indian exports, including textiles, gems, and machinery, is a shock to the system. Many observers see this as the biggest trade hit facing India in decades. As a result, exporters are scrambling and some foreign firms are reevaluating their India investments. India's response includes emergency financial packages and redirecting exports toward markets like Latin America, China, and the Gulf.

Technology and automation leveling the playing field

The narrative that India’s advantage lies in low-cost labour is becoming outdated. Automation, robotics, and digital manufacturing systems now matter more than ever. These technologies favour economies that offer stability, infrastructure, and regulatory predictability. India must shift its pitch accordingly: it needs to sell reliability and systems capacity, not just wage competitiveness.

…the manufacturing sector is held back by twelve barriers - from costly land and rigid labour rules to unreliable power, high logistics costs, and weak integration into global value chains. Each is solvable, but only if addressed in concert. This is where entrepreneurship matters: founders building in automation, clean energy, supply chains, and advanced materials are showing us how to bypass old bottlenecks and create new competitive advantages. Our conviction is that India’s next leap will come from scaling these solutions - not just to assemble, but to lead in global manufacturing.

Ankit K, founder of Capital A - India’s first manufacturing themes VC Fund and second generation entrepreneur (former promoter direct at Manjushree Technopack Ltd.)

Climate policy and carbon tariffs

Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is moving from concept toward enforcement. Goods like steel, aluminum, cement, and chemicals will soon face carbon levies unless exporters can prove low-carbon production. For India, which still relies heavily on fossil-based power, this poses a growing cost disadvantage. The expectation is to remain competitive in green-tech or energy-intensive exports…India must accelerate its transition to cleaner grids and more transparent emissions reporting.

Shifts in domestic and regional strategy

And of course, India is not standing still. Under frameworks like "Make in India" and the “National Critical Minerals Mission,” policymakers are pushing both industrial diversification and raw material self-sufficiency. The electronics and semiconductor sectors are expanding rapidly - India now assembles Pixel smartphones and AirPods and is building multiple chip fabs and OSAT facilities. These moves help boost industrial resilience amid a more fractured global trade environment.

At the same time, initiatives like the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI), involving India, Japan, and Australia, are creating new avenues for regional integration and supply‑chain diversification.

In Brief

India cannot afford to rely on a single engine of growth any longer. It needs a second pillar, and that pillar must be manufacturing.

This will require serious reform. At the national level, India must reduce trade barriers that make inputs expensive and isolate the country from global supply chains. Financial policy needs to deliver affordable credit, especially for mid-sized industrial firms. Labor laws must be restructured to allow flexibility without weakening worker protections. Clean, reliable electricity is a core export competitiveness issue, especially with carbon tariffs becoming reality in major markets.

States must take responsibility for execution. Land use planning needs to support industrial development, with better integration between factories and urban infrastructure. Growing mid-sized cities into industrial hubs will create jobs where they are needed most. Law enforcement and local governance must ensure that contracts are respected and property rights protected. No investor builds for the long term in a low-trust environment.

Beyond institutional reform, India needs a shift in mindset. For too long, policy has treated smallness as a virtue. Industrial policy has protected fragmentation, often at the cost of productivity. This approach is no longer viable. Scale, specialization, and global competitiveness are what matter in today’s manufacturing world. Policymakers must enable firms to grow, compete, and lead in global markets.

Finally, India must lean into global integration. That means welcoming foreign capital in manufacturing, not just in consumer tech and finance. It means easing cross-border movement of talent, simplifying trade rules, and creating enforceable legal structures for international commercial relationships. Global investors are looking for alternatives to China. India has the scale and the ambition to be that alternative - but scale alone is not enough…trust, predictability, and execution are vital.

The window of opportunity is open, but it will not remain so indefinitely.

Would request the author to cite sources for data and claims and ideally link to them.

The states that did do land re-distribution - WB and KL - ended up not industrializing and in the case of former even de-industrialized.